The elusive ‘bottom’

April 22, 2020 | By Kevin Smith, CFA

Seeking the bottom of the market is risky business.

The conditions that caused The Great Recession of 2007/2008 had nothing in common with our current crisis, but the feeling of watching stocks fall is similar. Investors are struggling with a complex blend of emotions, news media, and personal opinions.

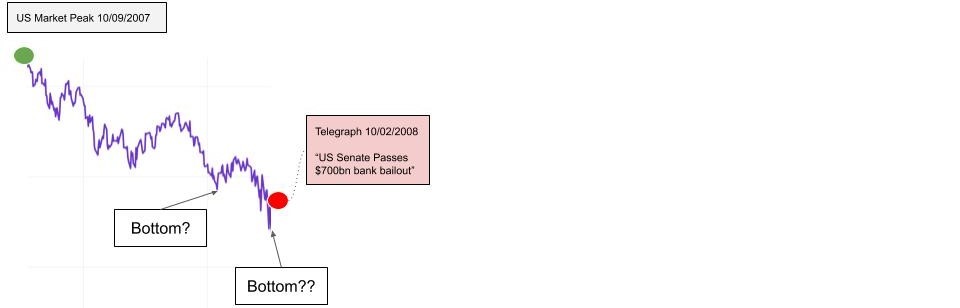

Both scenarios started with surprising and scary news. Lehman Brothers was the first domino to fall in late 2007, causing global panic. In February, 2020 we learned the virus spread outside of China. In both cases, it was too early to understand the scope of the problem. During the early stages of each crisis, encouraging news clashed with bad news as investors adjusted to new information in real time. Bottom searchers are hard at work.

It eventually became clear that both situations had potential to spiral out of control. The Federal Government stepped in with massive programs to avert disaster, but the potential impact to financial markets was not clear. The ‘bottom’ feels present but elusive at this stage.

The original bailout in 2008 turned out to precede a steep decline in stock market prices, followed by high volatility. The Federal Government stepped in once again with a big stimulus plan. The search for ‘bottom’ begins to feel desperate, and some investors talk about the potential of a total market collapse. Maybe the bottom is zero?

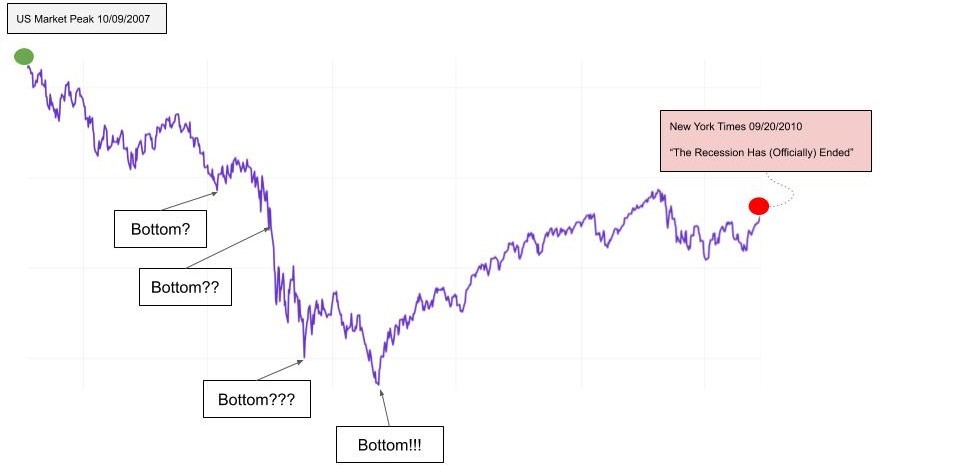

Another steep decline bounced back quickly, followed by wild swings and finally a positive trend. It may have been the first time investors felt confident they were past the ‘bottom’, almost two years later. If you have even faint memories from late 2009, it sure did not feel over at the time. Construction was still halted and jobs were scarce.

One year later the New York Times wrote “The Recession Has (Officially) Ended”. The ‘bottom’ had been reached, but stocks were still far from their high point in 2007. Most investors were highly suspect of the stock market and some vowed they would never trust it again. I heard some version of “Let’s wait until the market is more stable” nearly every day.

In hindsight, the bottom came and went in a flash. Buying stocks at that time felt more like trying to catch a falling knife than an opportunity to make a fortune. In the days leading up to the bottom, investors were selling their nest egg for half of its previous value. If they failed to gain enough confidence in stocks to buy again within the coming weeks and months, the losses would become permanent.

Let’s look at how four different investment strategies may have performed during this chaotic period.

Let’s pretend an investor had $50,000 available to invest in stocks at the beginning of the Great Recession. This amount is held in a diversified U.S. bond fund until sold to buy stocks. Here are four alternative strategies that could have been applied then and now. It cannot be known in advance which will produce the best results going forward, so our job is to determine which provides the best probability of a good result.

Investor A: buy at -10% drops

The idea is to have a plan to purchase stocks based on price declines REGARDLESS of what we think might happen next. It is simple: if the market drops -10%, buy $10k of stocks, if the market drops -20%, buy $10k of stocks, and so on. It usually feels like we are ‘buying too early’ and ‘things could get worse’. This strategy does not rely on anyone’s ability to predict the future, and it will be frustrating for those with confidence in their forecasting abilities.

The total value of the $50,000 using this strategy became $210,310 on 2/19/2020.

Investor B: buy after the ‘Bottom’

The nature of this strategy is to first ‘call the bottom’, then make investments. Because it requires feel and confidence in foresight, I can only estimate what an investor like this might have done. In this example, once there was confidence the bottom was behind us, the investor put a 1/2 of the money into stocks. After 6 months, the market muddled along and the investor put 1/4 into stocks, finally investing the balance after 5 months of choppy, sideways moving markets.

The total value of the $50,000 using this strategy became $194,200 on 2/19/2020.

Investor C: 100% stocks all the time

This highly disciplined, long-term investor stays fully invested in stocks at all times, meaning the $50,000 was immediately invested on the day just before the recession began.

The total value of the $50,000 using this strategy became $140,700 on 2/19/2020.

Investor D: do nothing

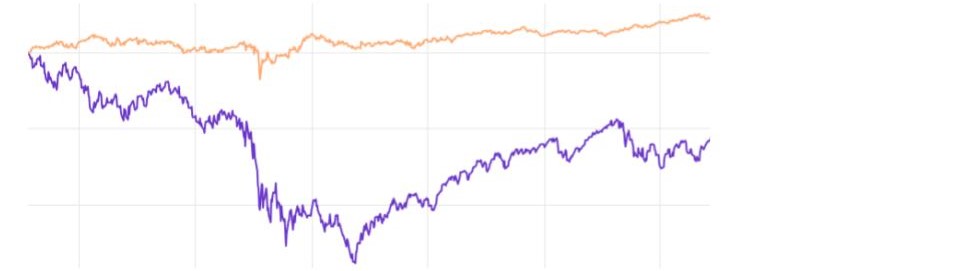

This strategy felt genius throughout the entire recession. Bonds (orange line) had a positive return while stocks plummeted (purple line). Investors with this mentality were not likely to get into the stock market before, during or after the recession. The result was a value of only $56,700 on February 19, 2020.

Simulated Results of Investing $50,000

Investor A: buy at -10% drops $210,310

Investor B: buy after the bottom $194,200

Investor C: 100% stocks all the time $140,700

Investor D: do nothing (bonds) $56,700

The lesson is not as simple as choosing the strategy with the best back-tested results. The results would be different in any other time period. For example, there have been long periods of time when the ‘Do Nothing’ strategy has vastly outperformed the others, and the assumptions behind ‘buy after the bottom’ are a rough guess about what that kind of investor might actually do. From my experience, those who wait for the right time to buy often never buy at all, so the assumptions may be generous.

Rather than choosing a strategy based on which one might work best at the current moment in history, we use a combination of strategies based on the purpose of the funds being considered.

Investor A: buy at -10% drops

This makes the most sense when introducing new money to stocks. We often use in combination with dollar-cost-averaging, which is a plan to move cash into the stock market every month over a period of months. When the stock market drops -5% or -10%, we make additional purchases. This strategy also works well when re-balancing from bonds to stocks.

Investor B: buy after the bottom

We never advise this because it is random. The ‘bottom’ is only known well after the fact so the results are more likely a function of luck than skill. If the market recovered faster, this strategy would have done far worse. It feels like a smart and proactive approach at the time, so it can be difficult to resist the urge to out-guess the markets. Even my simulated strategy was skewed by my preference to buy stocks after they have declined. Bottom seekers are often motivated by fear of losses, so they tend to wait until they feel safe, but markets rarely feel safe in the moment. Comfort comes after many years of consecutive positive returns, when stocks are expensive.

Investor C: 100% stocks all the time

Current investments should maintain targeted stock exposure as long as possible for the best odds of capturing returns in excess of cash and bonds. This strategy can feel foolish during recessions, but it is hard to argue with nearly 100 years of data illustrating the positive outcomes for disciplined long-term investors. Jumping out of the market at the wrong time and getting back in too late just one time can end in disaster.

Investor D: do nothing (bonds)

This makes sense if you need access to the money in the next 5 years. Anyone investing in stocks should be prepared to lose value immediately and for several years or more. If you want to make sure the funds are still there in the near future, this is the proper strategy.

Return to Blog Page