Broken Bonds

August 19, 2022 | By Matt Pierce, CFA

If we’re only ever looking back we will drive ourselves insane

As the friendship goes resentment grows

We will walk our different ways

But those are the days that bind us together, forever

And those little things define us forever, forever

From the English band Bastille’s “Bad Blood”

The word “bond” conjures to mind words like fidelity, constancy, or connection, and the financial term is used as a pillar of stability within portfolios and a ballast in stock market storms. Bonds have done that job and delivered stable returns for the last 40 years. I’ll concede I’m likely in the minority of individuals inspired to song by financial markets, and Bastille was likely not waxing poetic on the bond markets. Nevertheless, if this 40-year friendship ends, resentment will no doubt grow. Is it time we walk our different ways? Investor’s relationship with bonds may not define us forever but will certainly define portfolio construction in the coming decade at the very least.

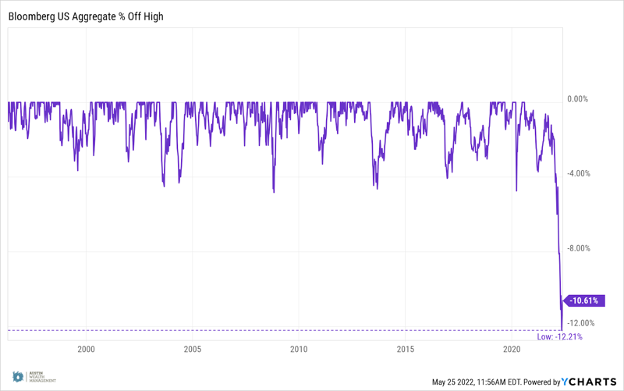

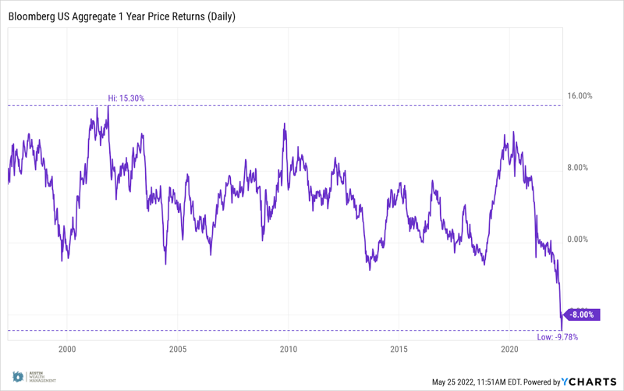

Looking at the historically abysmal performance for bonds to start 2022, bad blood might seem warranted. At the lows, one of the primary bond benchmarks was down just over 12 percent from its highest levels seen in 2020 with most of the decline taking place this year.

Before we completely jettison the friendship, some greater context may help mend our wounds and again bind us together. The extreme declines must be viewed against the backdrop of the significant gains seen in bonds. Bonds saw a rally into and through 2020, and at one point, were up over 13% on a trailing one-year basis during the more acute phases of the market turmoil resulting from the economic impacts of COVID-19.

Here, bonds mirrored the broader economy in which extreme moves in one direction beget extreme moves in the opposite direction. For example, GDP saw one of the sharpest quarterly contractions on record followed in short order by one the steepest rebounds. Seen below, the 10-year treasury rate responded in kind by plummeting to the lowest level on record, 0.5%, followed by the sharp reversal we’ve seen recently that has sent bond yields above their highest levels in 2018.

Given the magnitude of the moves, the pillar of stability role of bonds does appear to be on shaky ground, but within the broader context of a historically volatile economic backdrop, perhaps some leniency is warranted.

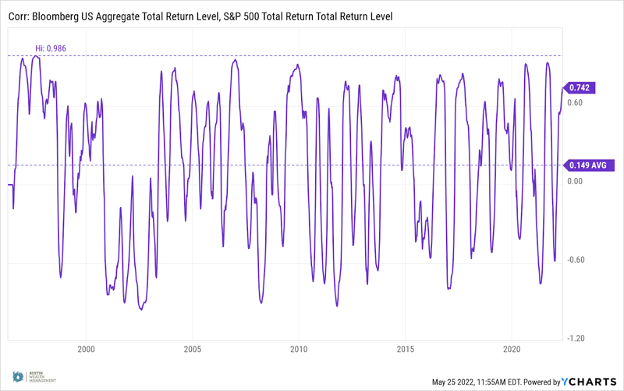

In addition to providing a source of lower volatility and stability within a portfolio, bonds often exhibit negative correlation to equities particularly when equities decline. While declines in bonds are not uncommon, falling in tandem with equities is rare particularly during bear market declines. At first glance, bonds appear to be falling short in their portfolio ballast role as well having provided no shelter from the equity storm. The chart below shows those rising correlations between stocks and bonds.

Before attempting to render a verdict, a further exploration of this stock/bond relationship might prove beneficial.

Stocks are said to live in the future reflecting the potential earnings of the market at large and its constituent components. As a result, stocks often anticipate broader economic slowdowns because slower economic growth generally equals lower earnings.

Bonds are similarly forward looking, and interest rates tend to be highly sensitive to expected changes in economic growth. Rates tend to fall when growth is expected to decline which causes bond prices to rise. In its simplest form, this is the core underpinning of the inverse stock/bond relationship.

This relationship helped explain much of the secular bull market in bonds, but 2022 has muddied the waters. Three qualifiers to this simple version may shed some light on the recent breakdown between this relationship.

- When interest rates move, are investors responding to the first order effect of growth as explained above or the expectation of the policy reaction by central banks those changes will elicit? Prior to 2022 this has been a distinction without a difference. However, this question becomes of greater importance if the answer is skewed toward the latter as policy responses become constrained by the second qualifier.

- Bonds are also highly sensitive to expectations of changes in inflation. Here too, growth and inflation changes have generally been a distinction without a difference which has meant the two mandates (inflation and employment) of the Federal Reserve have called for similar policy responses. Should these diverge, the two mandates come into conflict and may call for the Fed to tighten even in the face of slowing economic growth or create a desire to purposefully slow growth to combat inflation as we see today.

- As mentioned above, stock prices reflect investor’s expectations of future earnings for companies, and most attempts at fundamentally valuing stocks involve a forecast of those future earnings. To reiterate, this is the reason stock prices tend to fall in anticipation of declining earnings that result from an economic slowdown. Interest rates also play a critical function in the valuing of stocks. Since a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future, those future earnings need to be discounted back to the present to arrive at an estimation of an appropriate current price. Interest rates are the means by which this is accomplished. The implication is that when interest rates rise, the earnings may be unchanged, but the price an investor is willing to pay for those earnings may change. This is particularly true if the bulk of the earnings are projected to come further out into the future (think high-growth companies).

A more nuanced understanding of the relationship between stocks and bonds provides cold comfort in the face of this year’s losses, but armed with this clearer picture, we can continue to the last bit of context on the market’s behavior this year. More importantly, we can finally attempt to render a verdict about our relationship with bonds: bad blood or mad love.

The bond market appears to be grappling with two critical questions with vastly different implications and will likely remain captive to investor’s shifting views on their resolution.

One is shorter-term in nature and one longer.

Short-Term: Soft-Landing or Recession?

The Fed currently hopes to engineer a “soft-landing” in which they’ll be able to sufficiently cool demand to get inflation under control without triggering a recession. This seems a daunting task but taking that at face value leads to one potential outlook. Growth (and by extension, earnings) won’t slow significantly, or outright decline, and as described in our third qualifier above, stocks are merely “derating” (repricing) in response to interest rates rising. This would be an uncomfortable adjustment process particularly for those positioned toward more interest rate sensitive securities but would likely prove short-lived if the Fed is successful. The outperformance of value stocks versus growth for much of the year lends some support to this point as the former are more interest rate sensitive.

The less rosy scenario, the Fed is unable to stick the landing and tightening financial conditions triggers a recession. This would serve as an additional headwind for stocks as a combination of high interest rates and a declining earnings outlook would likely send equities to fresh lows. Slowing growth may help bonds, but if inflation remains elevated, bonds may not appreciate enough to offer much counterbalance to equities. The recent breadth of equity weakness, the slowing ascent of interest rates, inversion at several points along the yield curve, and pullback in commodities all suggest markets wrestling with a rising risk of this outcome.

Inflation could still prove to be “transitory”, but it seems clear policy makers got the messaging around inflation wrong. The tandem of midterm elections in which inflation will likely be a central issue and policy makers’ communication error around inflation is a potent policy cocktail. A Fed in damage control mode might be more likely to sacrifice their growth/employment mandate at the altar of their newly discovered zeal in combating inflation at least until such time that slowing growth or an outright recession becomes the more acute problem.

Assuming inflation comes down in either scenario, both could result in more short-term volatility and even additional downside risk for bonds, but they probably don’t spell long-term disaster. As detailed above, the recessionary outcome could even be bullish for bond prices as a result of more rapidly slowing growth and the expectations of an eventual Fed “pivot” toward accommodative policy.

Long-Term: Inflation, Cyclical Blip or Secular Shift?

The longer term question the market is mulling is the transitory nature of inflation. Is inflation, albeit less transitory than originally thought, still more a cyclical blip and owing largely to pandemic induced shocks, or is there a larger secular shift occurring?

The case for the former would cite factors like high debt levels, poor demographics in the developed world and China, and continued improvement in technology that will eventually reassert themselves as the dominant economic drivers. Once short-term supply issues dissipate, the economy will then resume its disinflationary trend.

The counterarguments would include factors like the trend toward reorganization of global supply chains if not outright deglobalization, global energy policy, and a rising role of fiscal policy as persistent sources of inflationary tailwinds that last well into the decade.

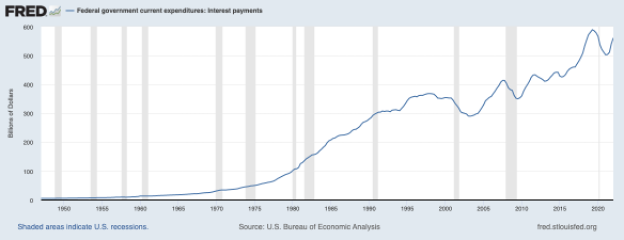

Another wrinkle is the fiscal state of the developed world at large, and the US in specific, and the degree to which rates can rise meaningfully in the face of massive debt loads and entitlement programs.

Despite coming off the lowest interest rates in US history, the Federal governments interest expense is near all time highs. Higher interest rates have the potential to create an untenable percentage of the budget directed to interest expense which could force the Fed’s hand at some point regardless of the state of inflation.

Doing any one of these countervailing forces and arguments justice is beyond the scope of this discussion, but fortunately, not necessary to answering our core question. What does this all mean for the economy and market, and in particular bonds and their role within portfolio construction?

To start, 40 stellar years can go a long way to foster unrealistic expectations. Maybe we’ve asked too much of this bond only to be set up for disappointment. Maybe some of the assumptions at the core of portfolio construction were oversimplifications bred by the unique circumstances of the last 40-years. Even absent these more macro factors, the starting point of the lowest rates in history should have implied muted return expectations for bonds going forward. Short of a massive deflationary shock that sends U.S. rates deeply negative, it’s hard to fathom a continuation of the tremendous total returns bonds have produced for the foreseeable future.

With better expectations, perhaps we can avoid the sting of resentment. Instead of ending things, perhaps it’s time we broaden our circle of friends, or in investing parlance, let’s look to “diversify our diversifiers.” The specter of uncertainty looms large, and the wildly unpredictable events of the last few years argue for a more broadly diversified approach rather than abandoning whole elements of an asset allocation. Asking bonds to serve as the sole source of diversification or stability within a portfolio was a tall order. Bonds as a critical piece within a larger group of assets, however, seems like the foundation for a continued beneficial relationships.

Return to Blog Page