Investing during a crisis: Coronavirus

February 28, 2020 | By Kevin Smith, CFA

Stock prices adjust to reflect the collective expectations of all investors. The basic formula for estimating a stock price is estimating future cash flows and discounting them based on risk. Lower expected cash flows = lower price. Higher risk = lower price.

Right now, it seems clear the coronavirus will impact future cash flows of businesses across the world and investors have increased their perception of risk. In combination, this drives prices down. We expect prices will likely fluctuate wildly as investors process this complex information.

As the Great Recession of 2007/2008 exposed frailties of the global money supply, the coronavirus will likely expose flaws in the global supply chain. New business opportunities will emerge in an effort to make systems more robust and less prone to disruption. People, companies and governments are resilient and determined to return to stable conditions, so we should maintain an expectation that a recovery will happen, and hopefully we will collectively learn to be more prepared for the next inevitable epidemic.

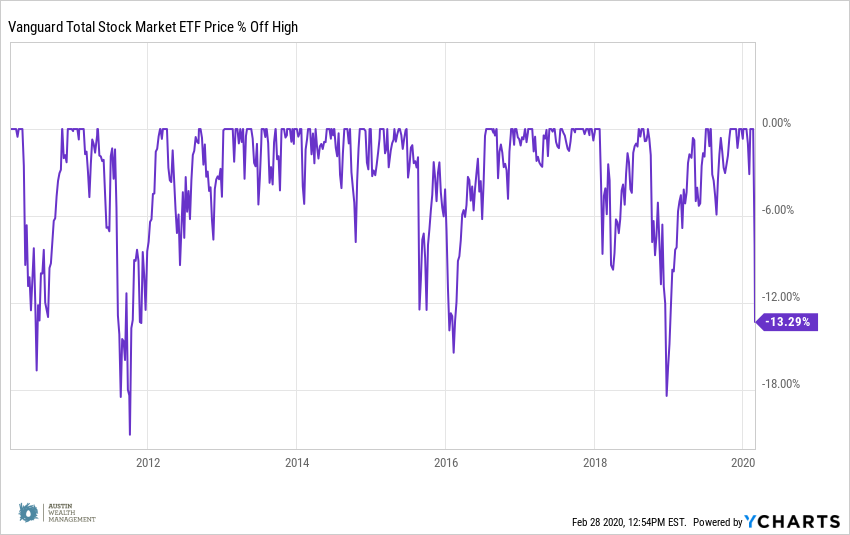

The chart below shows the last 10 years of draw-downs from each high point of global stock market prices. This week has been the biggest decline since the week of Christmas, 2018. The rebounds have often been as abrupt as the draw-downs, making market-timing a dangerous game. Josh Brown described this well in a recent blog post…

“The Flash Crash in 2010, the European Debt Crisis in 2011, the London Whale in 2012, the Taper Tantrum in 2013, the Ebola Scare in 2014, the overnight fix in the Chinese Yuan in 2015, the Oil Crash in 2016, Brexit in the summer of ’16 and the Trump Whipsaw later that fall, the Trade War’s onset in 2017, the ill-advised Jerome Powell remarks in 2018 – “we have a long way to go” – the assassination of Iran’s terror chief earlier this year – if you had panicked during any of these episodes, the embarrassment came swiftly and absolutely.”

The most successful investors who have been doing it for decades have a common message: stay calm, be patient, stick to your process, make gradual adjustments.

Natural questions are: How long will it last? How bad will it get? When will markets recover? What if this happens again, but worse? Nobody on earth has the answers, but a reasonable baseline assumption might be… conditions will likely get worse before they get better, and we will either contain it rather quickly or this could be the start of a prolonged recession, and history tells us something like this will happen again.

A well-constructed portfolio is built anticipating these types of conditions will happen, and does not require drastic changes to maintain a high probability of achieving the desired long-term results. For example, retirees should already have at least 5 years of spending reserves outside of stock markets, and working families should have emergency cash reserves and access to liquid investments.

The following are techniques we use to manage the risk of loss and take advantage of buying opportunities.

Allocation to Cash and Bonds

- Cash – maintain enough cash to deal with potential job loss and emergencies, and enough to cover major planned expenses in the next year or two.

- Bonds – maintain enough exposure to bonds to 1) cover expected withdrawals in the next two to five years, and 2) keep your downside risk to a comfortable level. For example if you have 100% stocks, you need to be prepared to see a 40% decline at some point. If you have 50% stocks and 50% bonds, you would see a 20% decline in the same conditions.

Diversification

- International – bad things can happen in any country at any time. An epidemic will affect all markets, but some more than others. Spreading investments across regions reduces catastrophic risk.

- Real assets – real estate and commodities tend to perform differently from stocks and bonds, and stand a better chance of maintaining value during periods of high inflation.

- Liquid alternative investments – these are typically hedge-fund-like trading strategies, most commonly trend following and managed futures. They tend to behave very differently from stocks and bonds, and offer the chance of positive returns in recessionary conditions. These quickly become unwanted in bull markets as they lag traditional stocks, but they need to be in a portfolio before a recession to be effective.

Cash Yields

- This is the cash you earn from holding investments. It comes in the form of dividends from stocks and interest on bonds. Although both are at historic lows, they provide a relatively stable source of income even as market prices decline, reducing the need to sell investments at a loss to cover expenses.

Rebalancing

- This means restoring your portfolio to its original target allocation. For example, if you started with 60% stocks, but the market increased and now you have 70% in stocks, rebalancing means selling 10% of your stocks and investing those funds in bonds. This process allows investors to maintain a more constant risk exposure.

- During a market drawdown, which we have recently experienced, this means selling bonds and buying into the stock market to take advantage of lower prices.

Deploying idle cash

- One measure of how expensive or cheap stocks are is the Shiller PE Ratio. This is a measure of the total stock market price divided by the average earnings of companies over the last 10 years.

- Investors who have saved cash in excess of their needs have an opportunity to buy into the stock market at relatively attractive prices. We encourage investors to do this systematically over time and consider accelerating on significant stock declines.

Posted in: Uncategorized

Return to Blog Page